Earth Artists, Ancient Earthworks, and Land Reclamation Sculpture from 1965 to 1985

This dissertation applies critical race theory to the well-researched history of “earth art,” a sculptural style utilizing natural materials at monumental scale, to explore the social and political context in which American artists adopted ancient, Native, and Indigenous earthworks as a visual arts practice in the 1960s and 1970s. Through three case studies of “land reclamation sculptures,” or major public commissions of earth art that rehabilitated industrial wasteland into public parks and works of art in the 1970s and 1980s, I situate the sculptures of Robert Smithson, Robert Morris, and Michael Heizer at the intersection of American national identity and landscape, environmental concerns and policy, and perception of Native people in popular culture. The convergence of federal public arts patronage, cultural shifts towards environmentalism, and mining waste management policies enabled suburban municipal agencies to commission the sculptures from established artists. The works’ longevity as interdisciplinary solutions to growing industrial wasteland in suburban communities constitutes significant achievements in the history of twentieth-century sculpture and public support for the arts, hile also attesting to the ongoing contributions of Native and Indigenous earthworks to the development of American visual art and identity in the twentieth century.

Despite the positive impacts of these projects, I contend that land reclamation sculptures, and the historic style of “earth art” from which they developed, generate meaning through adopting the materials and imagery of ancient “earthworks,” a term encompassing the mounds, terraces, dolmen, and petroglyphs constructed by pre-Columbian Native and Indigenous peoples across the Americas. In the eighteenth century, earthworks not yet lost to colonial expansion became a target of inquiry for early American explorers and archaeologists, who theorized that these structures came from a mythologized, prehistoric culture separate from living Natives. Published travelogues by writers from Thomas Jefferson to Theodore Roosevelt brought mass interest to earthworks, many of which were converted into state and federal historic parks to accommodate growing tourism to the American West.

My research demonstrates that, like most Americans in 1960s to the 1980s, earth artists and their viewers understood ancient earthworks culture through a mix of early American travelgoues and mythologies, contemporary heritage tourism to reservations and ruins, and popular stereotypes of the at-one-with-nature Native. In the same period, Red Renaissance cultural and Red Power political activism brought renewed national attention to Native struggles against termination policies and primitivist stereotypes. In self-consciously designing land reclamation sculptures in the image of ancient earthworks, the artists sought to legitimize their projects with ecological stereotypes of Native culture and notions of national heritage.

Chapter one reframes Robert Smithson’s artistic practice, often interpreted as spanning themes across deep time and geography, as entwined with American cultural tourism to Arizona and Utah in the 1960s and 1970s. Newly analyzed elements of his archive elucidate his travels to view Pueblo architecture, Hopi dance performances, and Ute petroglyphs in connection with his sculptures. Although Smithson’s adoption of ancient earthworks was rooted in genuine respect for and belief in the power of Native and Indigenous cultural forms, his sculptures manifested complex attitudes, shared by much of the white imaginary of his time period, towards Native peoples. Smithson’s tourism is considered as re-enactments of settler colonialism’s longstanding tradition of Western exploration and travelogue—a tradition that lives on in the countercultural novels, family vacations, and national parks informing the American identity. This dissertation positions Smithson’s engagement with Native American culture as historically constructed and socially informed, which in turn enhances understandings of his earthen sculptures as informed by a specific, constructed idea of the American West. At first theoretical and then practical, Smithson’s arguments for the application of earth art as environmental repair, and productive potential of historic earthwork imagery, occurred in response to efforts to source public and private patronage.

Although Morris fundamentally disagreed with Smithson that “art could reclaim wasted sites,” he was inspired by Smithson’s unfinished land reclamation projects. In Grand Rapids, Michigan, Morris designed Project X (1974) to stabilize a deteriorating reservoir hillside with a crossing walkway transposed from an X-shaped geoglyph built by the Nazca people in Peru, which he had traveled to see the previous year. The Women’s Committee of the Grand Rapids Art Museum coordinated private contractors, city departments, and a federal Art in Public Places grant to successfully transform the degraded municipal land into green public space.

The King County Arts Commission of Washington state, combining funds from the National Endowment for the Arts with the new grants offered through the 1977 Surface Mining and Reclamation Act, commissioned Morris to stabilize an abandoned, landslide-prone gravel quarry within a Seattle suburb. The sunken, terraced bowl of Untitled (Johnson Pit Mine #30) (1979) evokes the stepped agricultural andenes engineered by Incan people in Peru to create a work that maintains the deleterious scar of pit mining. Even though public reaction reflected controversy in the use of public money to commission land reclamation sculpture, the U.S. Bureau of Mines published an extensive report summarizing the project as a positive solution to transforming other strip mines. In the forty-five years since its completion, an attached-unit housing development has surrounded the four-acre Untitled (Johnson Pit Mine #30), increasing the importance of its open space and rainwater management to its community.

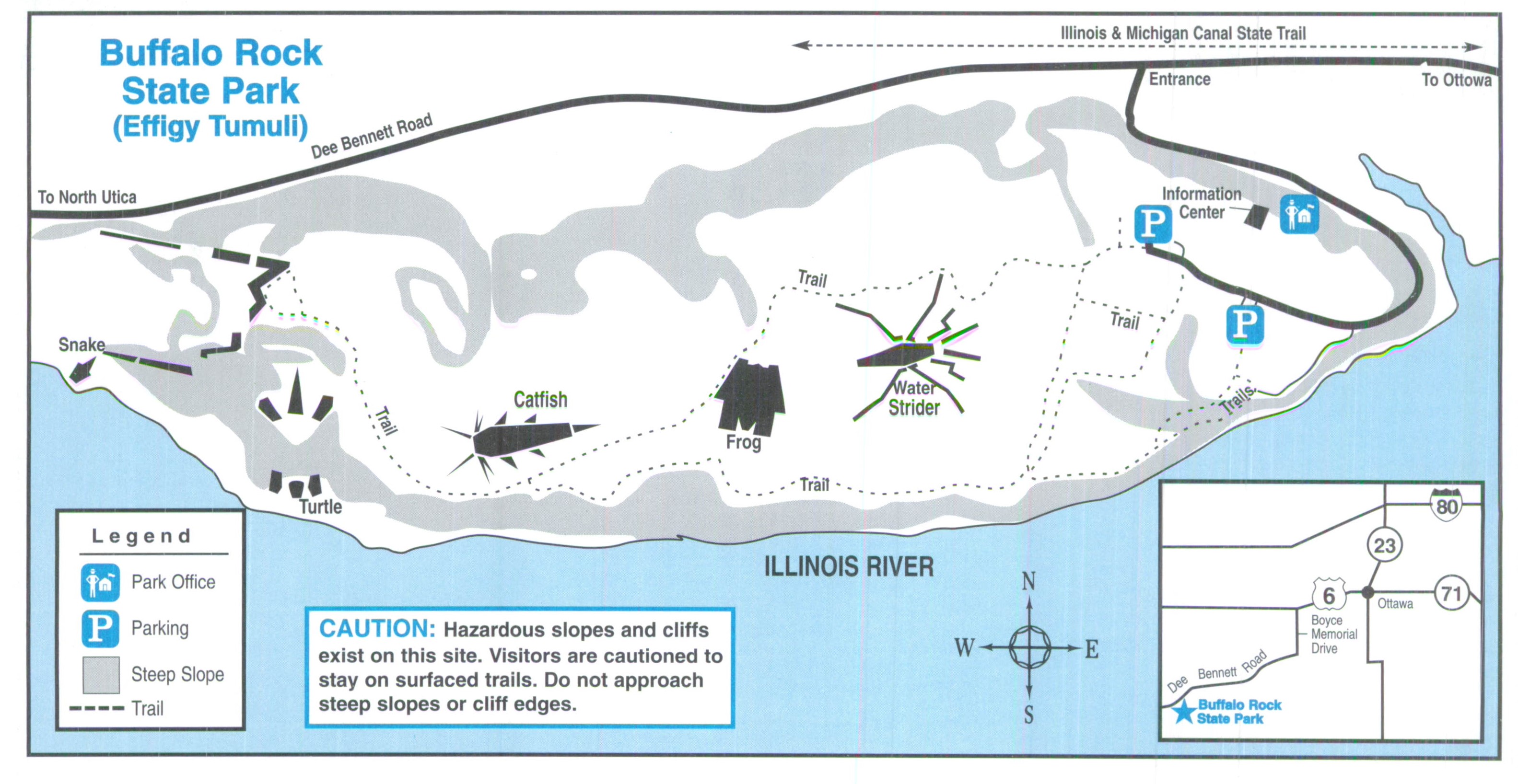

Chapter three turns to the largest land reclamation sculpture. Michael Heizer’s Effigy Tumuli (1983–1985) terraformed a 120-acre coal mine in Central Illinois into five animal effigies: a frog, a catfish, a turtle, a snake, and a water strider. Heizer, the son and field assistant of eminent Mesoamerican archaeologist Robert F. Heizer, combined the trapezoid forms of the nearby Cahokia earthwork city, named a National Historic Landmark in 1966, with imagery from petroglyphs he saw in the White River Narrows, Nevada. Illustrating the underinformed yet pervasive perception that Indigenous earthworks are abandoned, Heizer stated that the project was his “chance to make a statement for the Native American.” Effigy Tumuli was the last completed land reclamation sculpture before reductions in public arts funding and environmental policy foreclosed opportunities for future projects.

In response to the unique commissions afforded by national attention to industrial overburden—and in spite of personal convictions or ambivalence towards the use of sculpture for environmental repair—earth artists Smithson, Morris, and Heizer developed a particular model for land reclamation sculpture emerging from both sincere and superficial engagement with Native culture. This dissertation’s discussion of the popular perception of historic earthworks references a broad array of archives, media, interviews, biographies, and fiction to model an interdisciplinary application of critical race theory to postmodern sculpture. In the 1960s and 1970s, Indigenous earthworks, long present in national mythologies and newly accessible through paved highways, offered American sculptors an ecological and universal, yet distinctly American, symbol—an employable model for artists designing public sculpture for small communities. All free to the public today, the land reclamation sculptures illustrate the potential of interdisciplinary public art to offer both aesthetic experience and community space, while attesting to the historic importance of Native and Indigenous earthworks to the development of American visual art and identity in the twentieth century.

I apply critical race theory to the earth artists’ biographies, archives, projects, and statements to assess how they culturally perceived Indigenous people and earthworks. Heeding suggestions in Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s methodological guidebook for historians working with Indigenous material, I acknowledge my positionality as a white historian and prioritize Native voices, like Chadwick Allen and Katrina M. Phillips, for their key insights into the function and legacy of earthworks. I welcome feedback and commentary about this project. Please get in touch with me via my contact page.

You must be logged in to post a comment.